BUENOS AIRES, Argentina — The story of Jorge Griffa and Marcelo Bielsa knocking on the Pochettino family’s door during a scouting trip to see a 13-year-old Mauricio sleeping is relatively well known by now.

As Griffa remembers it, he and Bielsa had gone to Santa Isabel in the Santa Fe province of Argentina looking for talents to bring to Newell’s Old Boys in Rosario. While they were there, locals commented that a kid named Pochettino — from Murphy, about a 30-minute drive away — was the best young player in the area. The problem was Pochettino hadn’t been at the trial.

— Miller: How Spurs have been able to hold onto their stars

— Ogden: Premier League managers ranked

The duo, at the time raking the Argentine interior for young talent to compete with the country’s bigger clubs, didn’t want to leave any stone overturned in their search, and they rolled up to the Pochettino residence in the early hours of the morning.

“They showed us Pochettino sleeping,” Griffa said in a recent interview with ESPN. “At that time, he was huge for his age. He was as big as an elephant.”

Pochettino’s father had bad news for Griffa and Bielsa: His son was already set to join Newell’s bitter rival, Rosario Central.

“Has he signed?” Griffa asked. “No, he hasn’t,” Pochettino’s father replied.

Whatever precise persuasion techniques Griffa and Bielsa used, they were successful. A few days later, Pochettino’s father turned up at Griffa’s office in Rosario, according to Griffa, with his son’s registration card in his hand, and following a brief trial, “Poch” became a Newell’s player.

Is it a stretch to suggest that without that meeting and persuasion, Mauricio Pochettino would not have led Tottenham Hotspur to the Champions League final for the first time since 1962? Or that he would not be starting a new Premier League season as third favourite for the title, despite the team’s spending a fraction of the cash as their principal rivals? It’s too much to state with certainty, as every successful player or manager has to have breaks along the road. But the football schooling Pochettino received at Newell’s, as well as the shared identities and values that help define him and, by extension, his Spurs team, were vital to shaping his character and philosophy.

Pochettino has talked about the influence Bielsa has had on his career, but it was Griffa who laid the foundations for the Newell’s academy that forged footballing talents and minds such as Bielsa, Jorge Valdano, Gabriel Batistuta, Gerardo Martino, Gabriel Heinze, Maxi Rodriguez and, of course, Pochettino.

The 83-year-old Griffa might not be so well known outside of Argentina, and he doesn’t often seek the limelight for his work, but his stamp on the football world extends far beyond South America.

An hour-long conversation inside Griffa’s modest flat in the upscale Recoleta neighborhood in Buenos Aires flies by. Dressed in a black sweatshirt and neckerchief, Griffa is polite and warm, but he’s also imposing, full of conviction and passion. Even at his age, the former Newell’s defender is not somebody you would want to get on the wrong side of.

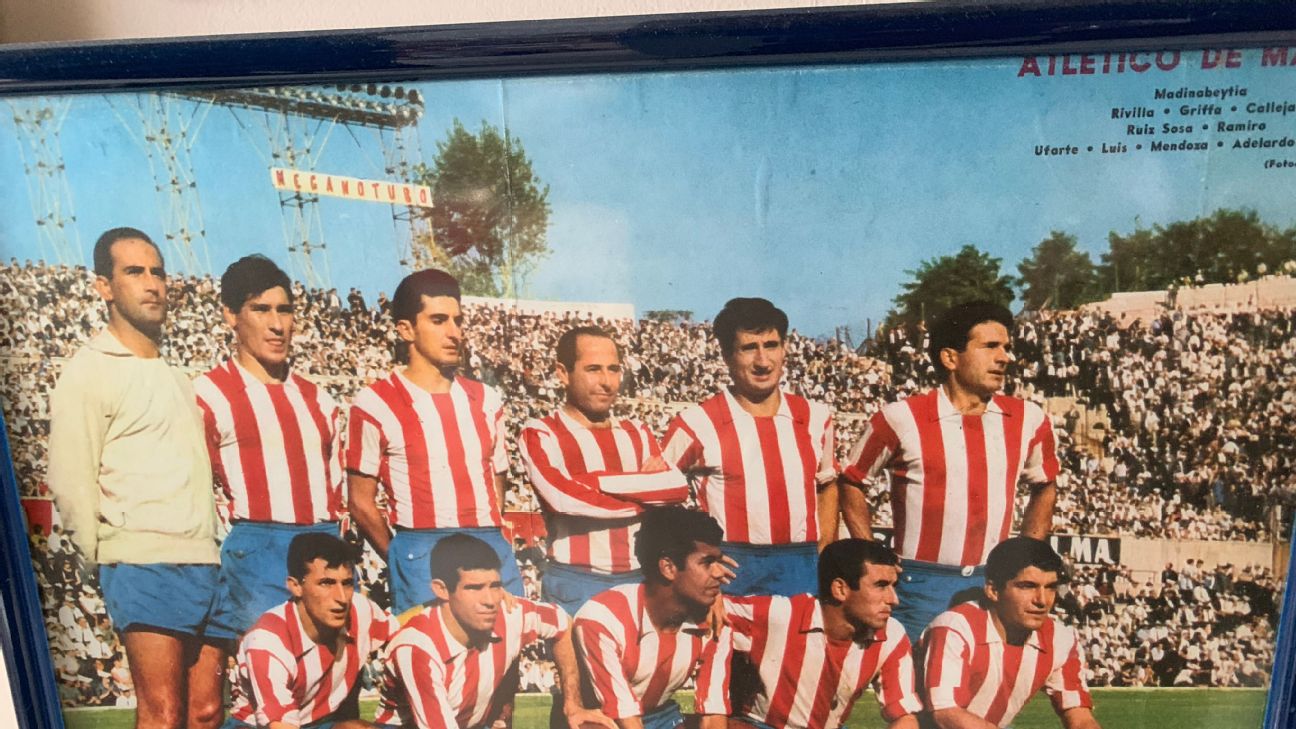

As with many other successful people in soccer and other spheres of life, there’s a clarity about his ideas. The conversation jolts from his role in recruiting and developing the likes of Batistuta and Carlos Tevez (for Boca Juniors) to becoming an Atletico Madrid legend and battling against the famous Real Madrid of the late 1950s/early ’60s as one of Argentina’s first successful defensive exports to Bielsa’s development from player to coach to persuading current Argentine president Mauricio Macri to purchase land where Boca Juniors could build a modern training facility and, finally, to the key elements he looks for in assessing a young player.

Griffa was a good player in his own right, and the same dedication that saw him later scour Argentina for players was seemingly ingrained in him from an early age. During his early career, he would travel more than an hour on a bus and, later, on his uncle’s motorbike from the town of Casilda to Rosario to attend training sessions at Newell’s. He also worked in his godfather’s general store “La Union” because “we used to earn two pesos, nothing, very little” playing for Newell’s.

After five years at Newell’s and a successful 1959 Copa America with Argentina, Griffa caught the attention of Atletico Madrid. During a 12-year career in Spain, Griffa won three Copa del Rey titles and La Liga in 1966, breaking Real Madrid’s stronghold on the title as part of a defence that conceded only 20 goals in 30 games that season. Tellingly, 50,000 turned up for his testimonial in Estadio Metropolitano.

Griffa describes himself as a “really hard” defender who could also play as a defensive midfielder and, in an era of limited sports science, says he played the majority of his career with a torn ACL after suffering the injury at the age of 21. After his playing career came to an end, he managed Newell’s for six months before recognizing that it wasn’t for him.

“I realized that I didn’t know anything,” Griffa said.

The realization that player development was more his thing would go on to benefit generations of Argentine players.

“It was the sacrifice of my life”

Griffa went about constructing a youth development system at Newell’s, building the training center on an old garbage dump outside of Rosario and going out to the countryside in search of players. The quality of Griffa’s work was vindicated in 1988, when Newell’s won the Argentine first division with a team made up exclusively of players formed in the club and, by extension, directly influenced by Griffa.

“I asked myself the following: How are we going to compete at a small club like Newell’s with River, with Boca, with Independiente, Racing and Huracan, who was big at the time?” Griffa said.

“We’ll do it in reverse,” he continued. “All the clubs have the desire to bring in boys from the interior, but they won’t go looking for them.”

Griffa built up a network of informants in the region and a promise to youth clubs that they would be rewarded if a youngster made the Newell’s first team.

“It was the sacrifice of my life, my children’s lives, my wife, everything, a whirlwind of things. Commitments, responsibilities, going to see different clubs in the interior — it was an immense job,” Griffa said.

Once the talent was identified and brought to Newell’s, the emphasis was put on players studying, which perhaps highlighted the prevalent culture and goes a little way to explaining why so many of the graduates — Martino, Eduardo Berizzo, Heinze, Pochettino — have had success as progressive and well-spoken managers.

“I always stressed the security of studying, [and that a career in] football was [only] a possibility,” Griffa said. “We had to try to get them to take the right path in the form not only of a footballing education but also a basic education that you need as part of society.”

The location of Rosario contributed to his scouting success, as the province of Santa Fe is historically rich in footballing talent. For example, Valdano recently suggested that Rosario deserved a Lionel Messi because of the intense footballing culture.

In 1976, then Argentina manager Cesar Luis Menotti asked Griffa if the Newell’s “B team” would represent Argentina at the Olympic Games regional qualifying tournament in Brazil in 1976. Griffa agreed, and the team finished third.

“There’s a triangle from the south of Santa Fe to the east of Cordoba and to the north of Buenos Aires. It’s a triangle in which there are normal families, families that are disciplined, well-intentioned and have very healthy environments, as well as good alimentation,” Griffa said, as if describing the Pochettino clan. “In other words, they have the basic principles and necessities.”

Griffa also had the eye for spotting talent.

“Does [the player] have good technique? Are they fast? Strong? They are the three over-riding conditions, but then I look for the ideal player: the technique and temperament, strength and coordination, physical and mental speed, intelligence and psychological balance.”

Griffa keeps in mind the concept of the ideal player, which he believes Messi and Diego Maradona have come closest to fulfilling. But more than his scouting ideas, when Griffa is mentioned outside of Argentina it is usually in association with Bielsa and their special relationship. Just last November, the Jorge Griffa hotel was unveiled at Newell’s training center, with the project funded by the Leeds boss, who insisted it be named after his mentor.

“Marcelo Bielsa was in the youth teams playing, and he came to me. In the first conversation we had, he said: ‘Are you Griffa?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ [He replied:] ‘If you came from Europe and you came here to manage the youth teams, you are crazy.'”

Griffa describes Bielsa as being a “rustic” defender in his playing days and adds that he possessed “tremendous commitment.” That Bielsa’s future was in football was clear, though it was not to be as a player.

“He came to me decidedly and said, ‘Jorge, I want to be a coach.'”

But Griffa didn’t want Bielsa to rush into coaching the first team like he had, telling him instead that he’d take him under his wing and develop his coaching potential: “You’ll be [a coach] in the first division, [but first] you’ll work with me, at my side, and at the right moment, you’ll make the jump.”

In 1990, after the duo undertook the mammoth recruitment drive and developed the players, Griffa went to the Newell’s president and told him that Bielsa was ready to be the club’s head coach. Griffa continued to guide his student . as the latter led the club to the 1991 Argentine Apertura title and 1992 Clausura championship, as well as to the final of the 1992 Copa Libertadores, with a team that included Pochettino, Berizzo and Martino.

“Marcelo had the requirements to be a great coach, as he now is,” Griffa said. “I also pushed him and put the brakes on in certain situations, a little like a father.”

Griffa’s work at Newell’s continued after Bielsa and Pochettino had long gone. He later developed talent at Boca Juniors, where the likes of Tevez, Fernando Gago, Ever Banega and Nicolas Burdisso came through the youth system during his 10-year spell with the club. Stints in Mexico, at Independiente and giving lectures in different countries followed.

Now, with Pochettino’s Tottenham Hotspur preparing for the Premier League season, Bielsa having reignited Leeds United, Mexico being reconstructed by Martino, Heinze one of Argentina’s most promising young coaches at Velez Sarsfield and Berizzo thriving with Paraguay, you’d imagine Griffa would be reveling in the fruits of the seeds he helped sow. But that isn’t the case.

It was striking that over the course of conversation, Griffa lamented how little time he’d spent with his family as he undertook his work in football with almost religious fervor. But after a spell in semiretirement, the football bug has refused to go, and he’s back where it all began: Griffa was appointed head of recruitment at Newell’s Old Boys back in February and, as he has done for the majority of his life, is once again looking for the next Pochettino, Tevez or Batistuta.